Seeing is Interpretation

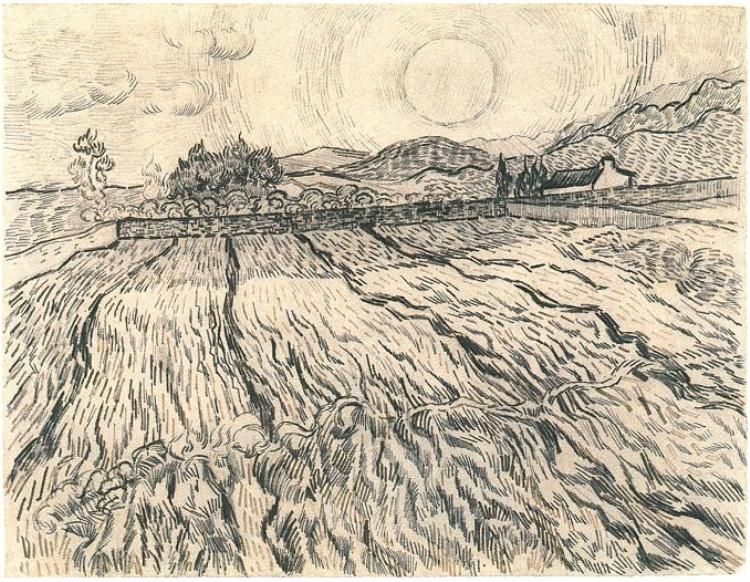

With functional vision, our minds are able to organize vast amounts of information to navigate 3D space. We're also conditioned to understand the representation of 3D space on 2D surfaces--we make sense of the depth portrayed in flat images on screens, walls, etc with the ease of constant practice.

As beginners at drawing, we may somehow expect to be able to translate 3D to 2D like a camera does. But most of us can't draw an illusion of space as automatically as our lifelong mental habits allow us to understand it.

This may feel frustrating, as expectations tend to. But it also offers a chance to pull back the curtain on the magician-mind and how it creates our experience of reality.

What we see is our interpretation of the world, not reality itself as if it were separate from the seer.

Every view we see organizes itself around the location of our eyes. Our drawing holds clues about where we were while we were looking at what we depicted.

As beginners at drawing, we may somehow expect to be able to translate 3D to 2D like a camera does. But most of us can't draw an illusion of space as automatically as our lifelong mental habits allow us to understand it.

This may feel frustrating, as expectations tend to. But it also offers a chance to pull back the curtain on the magician-mind and how it creates our experience of reality.

What we see is our interpretation of the world, not reality itself as if it were separate from the seer.

Every view we see organizes itself around the location of our eyes. Our drawing holds clues about where we were while we were looking at what we depicted.

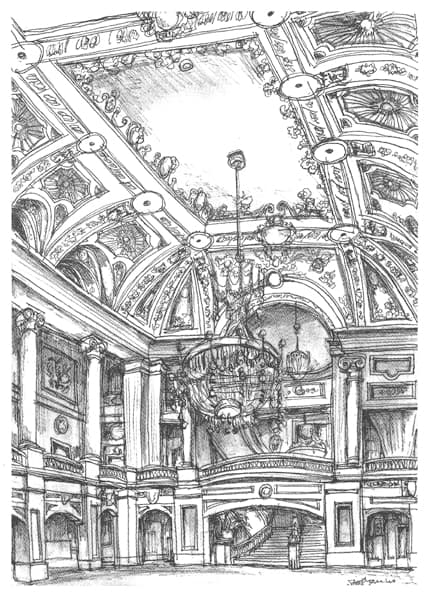

For instance, Stephen Wiltshire must have drawn this picture of the Chicago Theater from a position in front of the alcove to the right of the stairs (shown near the lower right corner of the page). How can we tell? He shows us just a sliver of the right side of the column to the left of that alcove, while further from him, on the other side of the stairway, plenty of the right face of the matching column is visible.

On the lower left side of the page, see how the angle made by the bottom of the pedestals along the floor rises slightly towards the rear corner of the room? The top molding above that first tier of columns angles a little bit downward towards the same corner. The artist's eye-level falls between them, below the height of the alcove arches--he shows a bit of their underside.

Without artist or viewer needing to be conscious of it, these consistent cues add up to give a sense of scale relative to human height and position, even without including figures in the composition.

I love watching how Stephen Wiltshire sketches--his focused, peaceable attention and his joy in seeing.

On the lower left side of the page, see how the angle made by the bottom of the pedestals along the floor rises slightly towards the rear corner of the room? The top molding above that first tier of columns angles a little bit downward towards the same corner. The artist's eye-level falls between them, below the height of the alcove arches--he shows a bit of their underside.

Without artist or viewer needing to be conscious of it, these consistent cues add up to give a sense of scale relative to human height and position, even without including figures in the composition.

I love watching how Stephen Wiltshire sketches--his focused, peaceable attention and his joy in seeing.

Some people have a particular gift for creating the illusion of space, recording exactly what they see. But the rest of us can learn this skill and play with it. It can be like studying a different language--something to keep the mind limber, without expecting instant fluency.

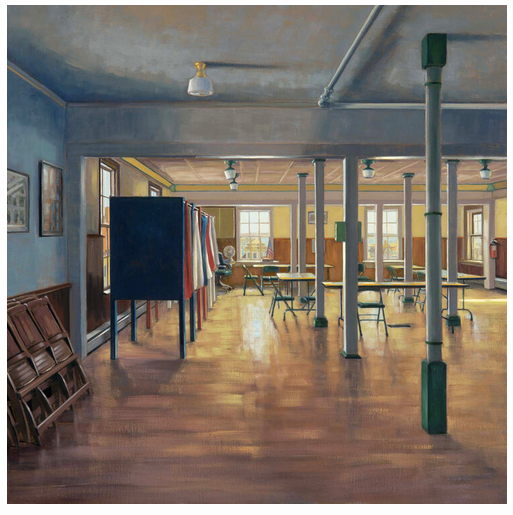

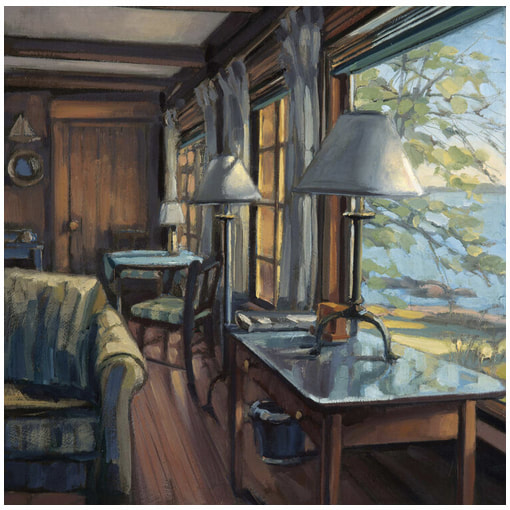

Drawing perspective can show us our habits and assumptions and put them on tilt for a moment, like a visual joke. Does the floor really wing up the page that steeply while the ceiling swoops down at such a different pitch? Those parallel posts--they're actually equidistant from each other--do they really look that much closer together at the far end than the near?

Beginners may try, unconsciously, to compromise between the angles and shapes they're really seeing and their habitual interpretation of 3D reality (the ceiling is not falling into the far wall etc). This makes for a flattened, tamed portrayal of perspective. It can help to experiment with exaggerating angles and asymmetries to correct for this bias.

Drawing perspective can show us our habits and assumptions and put them on tilt for a moment, like a visual joke. Does the floor really wing up the page that steeply while the ceiling swoops down at such a different pitch? Those parallel posts--they're actually equidistant from each other--do they really look that much closer together at the far end than the near?

Beginners may try, unconsciously, to compromise between the angles and shapes they're really seeing and their habitual interpretation of 3D reality (the ceiling is not falling into the far wall etc). This makes for a flattened, tamed portrayal of perspective. It can help to experiment with exaggerating angles and asymmetries to correct for this bias.

Election Eve, Alison Rector

Election Eve, Alison Rector Artists over the centuries have invented tools to help themselves translate from 3D to 2D more accurately--often variations on sighting compared to a grid or a horizontal/vertical reference.

Maine artist Alison Rector sometimes builds a scaffold out from her canvas to rest one end of her ruler on when the scene's vanishing points are located beyond the frame of the picture. (You might want to google 1, 2 and 3 point perspective if you're curious about vanishing points).

As described during our meeting, you can use an imaginary clock face hung on a transparent wall between you and the view to help gauge angles. It can help to use two pencils or thin skewers, one to hold a horizontal or vertical standard (at 3/9 or 12/6 on the imaginary clock) and the other to overlap the angle you're looking at (how many minutes +/- is that?). Be sure to check that you're not tipping your reference stick(s) into the space--keep them on the plane of that imaginary transparent wall in front of you.

Maine artist Alison Rector sometimes builds a scaffold out from her canvas to rest one end of her ruler on when the scene's vanishing points are located beyond the frame of the picture. (You might want to google 1, 2 and 3 point perspective if you're curious about vanishing points).

As described during our meeting, you can use an imaginary clock face hung on a transparent wall between you and the view to help gauge angles. It can help to use two pencils or thin skewers, one to hold a horizontal or vertical standard (at 3/9 or 12/6 on the imaginary clock) and the other to overlap the angle you're looking at (how many minutes +/- is that?). Be sure to check that you're not tipping your reference stick(s) into the space--keep them on the plane of that imaginary transparent wall in front of you.

Accuracy isn't an end in itself, though. Distortions and variations on expected ways to portray space can express something important about what and how the artist is seeing. Also, the post-Rennaissance Western approach is far from the only way humans have come up with to show what they observe about how things-in-space fit together.

Practice

I'd suggest starting with a study of corners. Sketch the corner of a room, showing both ceiling and floor, checking angles. Keep it simple. Then move your position and draw it again. Also, try drawing the corner of something smallish, like a table or an ottoman, followed by drawing the corner of something bigger, like a building.

Otherwise, as you draw whatever you like, just bear in mind that things which are closer appear bigger. And check where your eye-level falls, noticing what you see the top surface of, what you see the under surface of, etc.

Take you time, and enjoy yourself! What a lot there is to see.

Otherwise, as you draw whatever you like, just bear in mind that things which are closer appear bigger. And check where your eye-level falls, noticing what you see the top surface of, what you see the under surface of, etc.

Take you time, and enjoy yourself! What a lot there is to see.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed